Riots Aren't Civil Disobedience

Flattening all protest into a simulacra of the Civil Rights Era is dumb

If you have eyes and an internet connection, you’ve been bombarded over the past month or so with infinite images of people in keffiyehs and face masks doing various things. Some of them are holding signs, some are chanting, some are creating checkpoints and establishing authority over formerly public spaces, and some are occupying and refusing to leave private spaces owned by their colleges.

Some are getting arrested. Whenever this happens, it’s frequently described as “civil disobedience,” implying that any noncompliance to authority in any circumstance is “civil disobedience.” I found this annoying, and now you’re going to read an essay about it.

What is Civil Disobedience?

Of all the forms of protest, civil disobedience commands the most reverence - and with good reason. It’s the bravest and most elegant form of protest - putting your liberty on the line to stand up to injustice, without causing harm to others in the process. It’s a very ancient form of protest - in Sophocles’ play Antigone, written in 441 BC, we see Antigone giving proper burial rites to her brother after her father forbade it, and being executed as a result. We can find examples in the Bible - the prophets of the Torah are constantly denying, rebuking, disobeying, and being cruelly punished by the various regents of the ancient Levant. You can even see it in Colonial America in Salem, where farmer Giles Corey was accused of witchcraft - rather than confess and admit to a crime he didn’t commit, he defiantly suffered the punishment of being crushed to death. Each time he was given the opportunity to confess, he asked for more weight to be placed upon him.

But this tactic of “refuse to comply and suffer the punishment” didn’t get an official name until Henry David Thoreau put it on the page in 1849. Thoreau was an arch-individualist - he did not wish to contribute to evil or oppression and resented the federal government’s acceptance of slavery and their recent invasion of Mexico. In Resistance to Civil Government, he argues:

“Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them? Why does it always crucify Christ, and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?”

(This does of course make me wonder if Thoreau would be writing DO 👏 BETTER 👏 while Instagramming on Walden Pond if he were alive today.)

In Thoreau’s case, he refused to comply with the wishes of the government he despised by refusing to pay taxes. His work inspired activists like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. to apply the tactic of civil disobedience to their own righteous crusades for individual liberty.

Gandhi led tens of thousands of Indians on a march to the sea where he collected salt in defiance of the English Salt Laws, which prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt. He was arrested and many of his followers were savagely beaten by British forces. He showed the brutality of British occupation to the world.

King led a broad coalition of civil rights activists to overthrow the Jim Crow laws of the South and eliminate the racism baked into American laws and institutions. Two of the most effective and memorable campaigns in this era revolved around civil disobedience - Rosa Parks’ famously interrupted bus ride, where she was arrested for the crime of refusing to give her seat to a white man, and the Greensboro Sit-Ins, which started when activists refused to leave a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter until they were served.

It’s worth noting that both these acts of civil disobedience took place between 1955 and 1960 - long before the “Summer of 68” that pop culture decided was the height of the “protest movement.”

Civil Disobedience vs Protest in General

As previously mentioned, we’re in the middle of a wave of college protests. I’ve been extremely frustrated to see all protest that includes confrontation with police or someone getting arrested described as “civil disobedience.”

All of the examples described above have one thing in common - the act of disobedience is directly tied to the law or policy that the actor finds unjust. Segregated lunch counters are wrong - so people sat there and suffered the consequences. Preventing the Indian people from collecting and selling a vital nutrient like salt is wrong - so Gandhi collected salt and suffered the consequences.

But the edges get fuzzy when the protest becomes removed from the actual policy or law being protested. Is it civil disobedience to get arrested for blocking a sidewalk? If your problem is with laws preventing protest groups from blocking sidewalks, it’s absolutely civil disobedience to block a sidewalk and get arrested for it. If you’re protesting factory farming and you block a sidewalk and get arrested for it, it’s not civil disobedience.

So let’s do a little Goofus and Gallant.

Gallant: Woolworth Counter Sit-Ins

This picture is famous for a reason. The people at the counter aren’t screaming slogans, wearing face masks and bike helmets, wielding Rubbermaid tower shields, or trying to hit the moral monsters attacking them. They are enduring the evil, and letting everyone in the world witness that evil, while maintaining stoic dignity.

Goofus: The Girl Who Would Be Hipster Ho Chi Minh

The first hilarious and obvious difference is the veritable forest of microphones in front of our aspirational Chairman Maosy - the deference and care with which these protestors are treated. The strange thing is that there’s no opprobrium from the people around them - what’s affecting about the photo of the Woolworth’s counter is that you can see EXACTLY what the protestors are protesting - the wickedness of that crowd, the laws and social structures that empowered them, and the culture that cultivated their cruelty.

The second is the total disconnect between the actions these protestors are taking and the issue they are protesting about. “We took over this building on campus because… uhh… BDS? End capitalism? Also you need to honor our meal plan after we have seized a building from you, and refusing us makes you Hitleresque.”

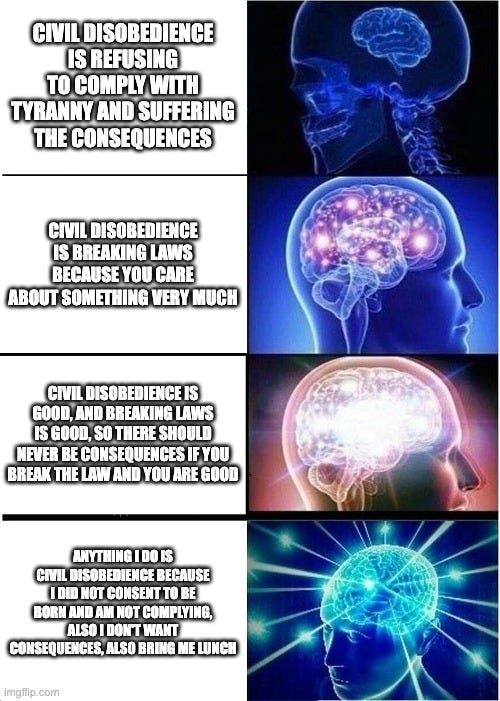

There is no element of non-compliance here unless you get very galaxy-brained.

Why is it like this?

As I mentioned earlier, most of the revered and remembered acts of civil disobedience in American history took place during the Civil Rights Era. But there’s a problem with the way this history is remembered in our popular imagination - for some reason, Americans collapse the entire period from 1955 to 1970 into one “era,” but those fifteen years include several different eras of social change. Landmark civil rights laws like the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were all passed by 1965. The Vietnam war protests, SDS, Weatherman organization, Days of Rage and Summer of Love all happened years after those civil rights battles were already won.

This period has been mythologized and idealized by popular culture (anything that lovingly refers to “The Movement” is in this zone), to the point that people just don’t remember the intense political violence. By 1969, political bombings in major cities were a regular occurrence. People forget that the post-Civil-Rights-Laws radicals loved Ho Chi Minh and Mao (other than Angela Davis, most were too hip to be flat-out Stalinists), and that they were fighting for an actual revolution in America. Check out Bryan Burroughs’ Days of Rage for a deep dive into the beliefs and plans of America’s favorite radicals. These sociopaths are revered as folk heroes and enjoy a halo effect from their temporal proximity to the actual Civil Rights movement.

Today’s protestors claim the mantle of civil disobedience but are actually inspired by the revolutionary memory of the late 60s and 70s, not the road paved with suffering that civil disobedience pioneers walked down in the 50s and 60s.

So please, if you’re describing a protest, just call it a protest. If you’re describing a building being seized by protestors, call it “protestors seizing a building and refusing to leave.” Don’t give aggressive disorder the same status as civil disobedience. It’s a noble tradition that deserves better.

Thank you to the helpful commenter who noted that I got the Antigone story exactly inverted, I edited the post to correct that.

Thoughtful, informative and enlightening… heartfelt thanks! 👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻😊